|

Yesterday I had the privilege of meeting some of the bright young students of St. Edmundsbury Church of England Primary School. One of many questions I was asked was by the USA Class: "How long have you been a scientist". Initially I answered that it was after I graduated from college, but that is not true - that was when I started to get paid as a scientist, but I was a scientist way before then. It didn't hit me until later, when I thought long and hard about that question. I believe that as kids when we start to learn about the world around us, ask questions, especially the "why" questions, we are already scientists! Many people lose that curiosity over time, but scientists retain that.

Growing up, I wanted to learn more about forests and the animals, how the soil I stepped on looked like if we were to dig into it. As a kid I received my education through personal experience (long walks in the woods with our dog Sasha, making personal observations) or through nature documentaries, and asking lots and lots of questions of people around me. So, when did I become a scientist? The answer: I never stopped being one.

0 Comments

On Monday February 20 I will be having a Zoom session with a school (or more?) in the UK. I am so excited to share with them the journey, the science and what it's like to be here. One thing is for sure: there is unparalleled beauty right here from station as shown in the above photos. I very much appreciate being here, to be doing science, to be part of the Palmer Station community, and to be surrounded by the majesty of the landscape.

The cute "tuxedo" penguins, the Adélies, were the only penguin species in the Palmer Station area in the early 1970s. Large areas of Antarctica, though far away, has unfortunately also suffered from rapid warming. Adélies are an ice-dependent species, but sea ice is not as thick anymore nor does it last as long as it used to. This means that other species of penguins that are not dependent on the ice are able to get established. It was the early 1990s when a different species of penguins, one from a warmer climate, were first sighted: the gentoo penguins. Now the gentoos have increased in numbers dramatically, while the populations of Adélies have decreased by 90% or more. In fact, gentoo penguins now outnumber the Adelies - a staggering shift in penguin species in the Palmer Station area! Adélies truly are the harbingers of change.

Researchers, such as Dr. Megan Cimino and her team, Darren and Megan Roberts, study where penguins hunt for food, the types of food they eat, how many of the chicks survive to the fledgling stage (i.e., "teenagers"), and much more. Much of the work is part of a study that has been ongoing since the 1970s! Though there are lots of data, new tools opens up ways to answer new research questions (e.g., use of robots to find krill - the main source of food for penguins). Very cool work (pun intended!). Photos feature the "teenage" penguins, some still losing their chick down coat in interesting patterns (e.g., see "crop top" penguin. :) This post is waaaay overdue! Earlier in the season we were lucky to be surrounded by many whales. I finally was able to use my nice telephoto camera to get these shots. Whales are wonderful, smart mammals that learn from each other. For instance, these whales have learned how to create "bubble nets" in the water to hunt for krill. What is a bubble net? Imagine they swim in a circle beneath the surface while creating bubbles through their blowholes (i.e. their nose) on the top of their head, and then those bubbles rise up to the surface. Krill can get caught within that circular screen of bubbles. Now, the pattern is are actually more spiral-shaped, but there are many other bubble net shapes also!

The humpback whales near station seem to do hunt using the bubble nets, but not all whales do! A research team on station (Ross, Jenny, Ariana, Logan) are studying the whales here, their behavior (such as bubblenet feeding), how related they are and their overall health. Pretty neat! All samples (including those collected on February 6) will be sent back to the US for a lab temperature experiment. Based on our field warming experiment (with the open-top chambers), we know that soil microbial activity is affected by warming. The lab experiment can help address who is responding the most (or least) to warming! We use a method called quantitative stable isotope probing (or qSIP for short), whereby we can assess how fast (or slow) microbes grow based on how heavy their DNA gets.

Thank you Keri and Doc Joe for helping Soil Team 6 (Sara and I) collect samples for a cool (haha, pun intended) lab experiment. The Wilson's storm-petrel is a small seabird, about the size of an American robin (or the blackbird in Europe). What I love about these agile birds is that their feet pitter-patter on the ocean surface to find food - they are like graceful "dancers". I never tire of watching these pretty little birds.

Today we collected samples for an incubation experiment for my postdoc Dr. Alicia Purcell. It was a beautiful day! To get to Litchfield we go on a Zodiac - it is the same type of inflatable boat used by the military, the F-580. With a 60 horsepower engine, we arrived at Litchfield in no time. However heading back we went through some brash ice, so best to slow down!

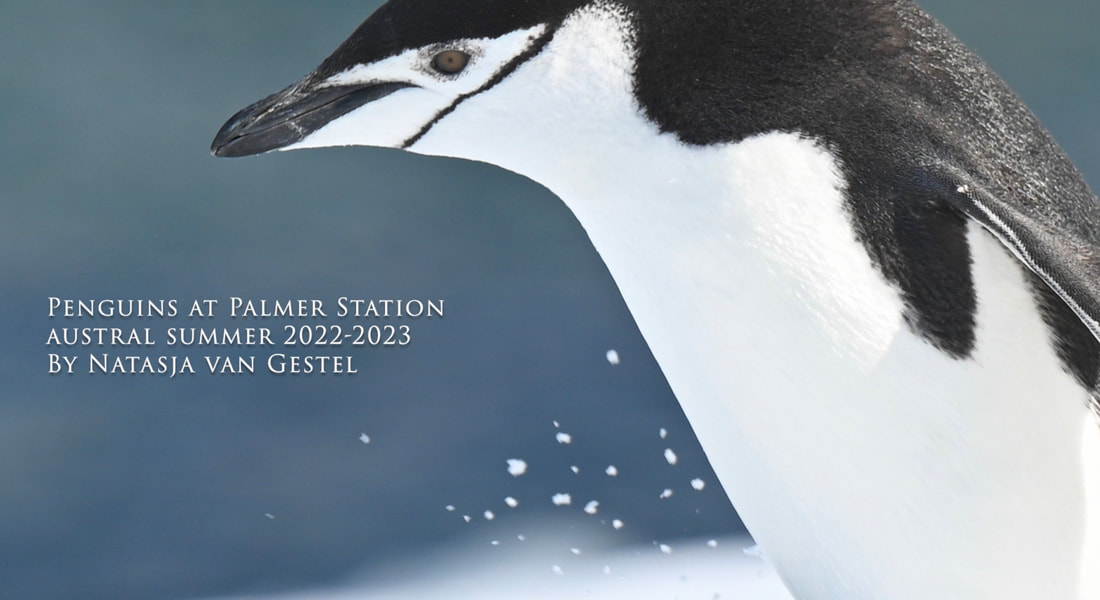

Thanks Hannah, for helping us with sampling today! And Sara, great job driving the Zodiac back onto the trailer: a 10/10 score!!! The penguins around station never cease to amaze me. They can be graceful one moment, and clumsy the next. When they are in the water they sometimes porpoise: they shoot out of the water, are airborne briefly, then return back into the water. Such a pretty sight. They sure make my summer. I hope you enjoy my penguin video on instagram.

A science team on station is collecting data on transects, week after week, and year after year. The small vessel they use is Hadar, a rigid hull inflatable boat or RHIB (see first photo). Data are collected to understand more about the ocean environment that is home to penguins, whales and seals. Today - while I was helping out - we saw heavy penguin traffic on a bergy bit (i.e., mini-iceberg). Penguins shooting out of the water to land on the ice (with some scrambling involved sometimes), and some dropping right back into the cold water.

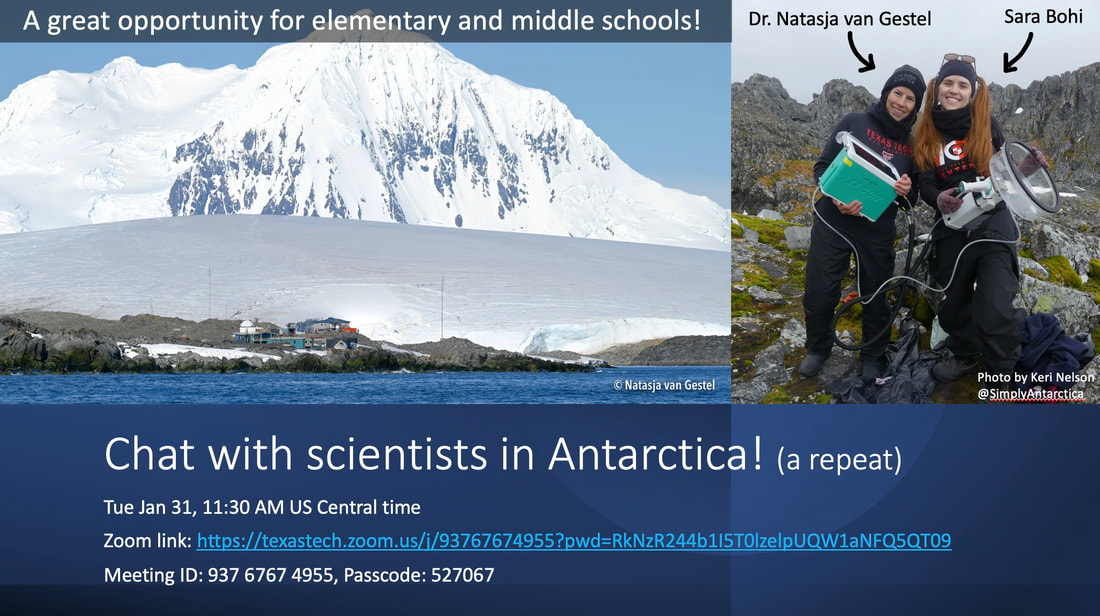

It is pretty amazing how a penguin has so much speed and strength that it can porpoise - a movement whereby a penguin is airborne for just a moment before it dives right back in. Incredible! Thanks Sneha and Matt for having me join on Hadar. For those that missed my presentation the first time around, just a quick reminder that I will be using the same presentation tomorrow, Tue January 31. So, this is a second-chance opportunity for those who couldn’t watch it last time. Attached is the ad for the presentation. For those in Europe, I will do one more presentation later (stay tuned)

Zoom meeting info for tomorrow: https://texastech.zoom.us/j/93767674955?pwd=RkNzR244b1I5T0lzelpUQW1aNFQ5QT09 Meeting ID: 937 6767 4955 Passcode: 527067 |

About meGrowing up watching nature documentaries, I find myself now immersed in nature's splendor. As an ecologist I study how ecosystems function. Here I share with you my love of doing research in Antarctica - a place of sheer beauty Older posts

March 2023

|